During the 20th century, Brazilian music gained worldwide recognition because of its syncopated rhythmic approach, singable melodies, well balanced harmonies and dances attached to its performances. Among countless musical genres that are part of Brazilian culture, Samba and Bossa Nova are ubiquitously the most known in the world, being played in almost all countries.

My experience in United States during my master’s in Jazz Performance has shown me some issues that non-Brazilian musicians face when playing Brazilian music. The main ones I could notice are lack of understanding of the rhythmic approach and lack of use of common Brazilian rhythmic figures. The first issue relates to how Brazilian musicians understand Samba’s and Bossa Nova’s main accents and the second one relates to the most common patterns played by an instrumentalist in a specific genre or style. In short, although syncopation is a strong characteristic of Brazilian music, there are some particular specificity in Brazilian culture that differs from other syncopated genres tagged as Latin music. This text will discuss the Brazilian music main accents.

At this point I will include the Choro, which is a less known Brazilian genre that precedes Samba and Bossa Nova, because they share several characteristics.

One of the similarities among Choro, Samba and Bossa Nova is the 2-feel with a slight accent on beat two. This accent can be related to the bass drums played at samba schools. As a general rule, the drum that plays on beat two is tuned at a lower pitch when compared to the drum that plays the beat one. The result is a natural accent on beat two. This accent also occurs on the pandeiro, which is the most common percussion instrument in a Choro ensemble, and less noticed on the drumset in a Bossa Nova ensemble.

Here I will point out the first main characteristic of Brazilian music which is the downbeat with accent on beat two. When playing a Choro, a Samba or a Bossa Nova, the musician must feel the downbeat and the accent on beat two. The amount of accent will vary according to the genre, being more prominent in Choros and Sambas and less noticed in Bossa Novas. Even if a particular rhythm does not have someone playing the beat one like the Partido Alto, the musician must feel the downbeat.

Try to hear the 2-feel and the accent on beat two in the following examples.

Samba –

Choro –

Bossa Nova –

Partido Alto groove –

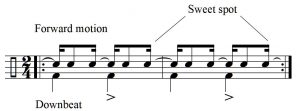

The second main Brazilian music characteristic is what I call forward motion. The forward motion is the syncopation of the sixteenth notes* that brings a forward movement to Brazilian music. The general Brazilian music feel that one can hear in a Choros, Sambas or Bossa Novas will be the result of the downbeat and the forward motion.

The very last sixteenth note of a measure is what I call the sweet spot. It is the place where melody and harmony will hit most anticipations.

Bringing these ideas to an actual performance, here are the instruments roles:

- Bass, bass drums and other low-pitch instruments will play mostly the downbeats

- Comping instruments, melody and high-pitch percussion instruments (e.g., hi-hats, snare, etc.) will play the forward motion.

Check the following recording and listen to each instrument trying to find their roles in terms of downbeat and forward motion. In addition, try to hear anticipations in the sweet spot.

I know there is a ton of things to learn to play Brazilian music as we play in Brazil, but I hope this explanation gives you a good start.

Hamilton Pinheiro

* Brazilian music charts in Real Books and Fake Books are written in 4/4 time signature, but most Brazilian musicians prefer to write in 2/4. This means that the measure will be filled mostly with sixteenth notes.